The ultimate guide to sea fish handling in UK waters

It’s no secret that marine anglers are some way behind our freshwater counterparts when it comes to fish handling, and much of that is down to the history of the sports. Freshwater fishing evolved into the catch and release sport fishing long before sea angling, and some disciplines such as Stillwater carp fishing have never been anything but a sport fishery.

In the days of taking every fish for the table, handling was a low concern. Now we are incentivised to maximise the post release survival of fish when practicing catch and release, it needs to be a priority.

Even when taking fish for the table, humanely dispatching of the fish not only reduces unnecessary trauma and suffering for the fish, but maximises quality of the meat, so this guide will talk about dispatching of relevant species.

This serves as a general guide, with some species specific items. Where possible, we link to more detailed resources for specific species, such as the work that has been done by the Shark Trust on sharks, skate and rays, and the work in progress by the Angling Trust on bass.

Contents

Venomous species

Thankfully, the UK has very few venomous species, but specific care must be taken of those few, the most prominent of which are the weever fish (greater and lesser) and the common stingray. As a handling guide, we’ll skip over the various jellyfish that pack a big sting that can appear in UK waters.

If you are not confident in identifying the species you are handling, exert increased care. Handle with a wet cloth, be sure not to touch any spines, attempt to unhook in water without even touching the fish where possible. With a northern shift of species occurring, any ‘oddity’ could be a new species to our waters that is venomous or can otherwise injure the holder if handled wrong. Other species like spurdog have barbs that will do reasonable damage without proving venomous.

Greater and Lesser weever fish

The most likely one to encounter will be the smaller, lesser weever fish. Greater weevers are a deeper water species and only caught in numbers on boats from the South West. Greater weevers, owing to their size, are also easier to handle. Both species have just one key spot to avoid – a protruding black spine in their dorsal fin.

This spine will cause serious discomfort, with more severe reactions up to and including temporary paralysis in a small number of incidents. Like jellyfish, pouring warm water over it can help alleviate some pain but immediate medical attention should be sought.

With larger specimens, the fish can be gripped in a way to keep the spine away from you, taking care to not accidentally come into contact whilst using the correct tools to unhook the fish before releasing it back to the water (or dispatching, in the case of greater weevers that some people like to eat).

For smaller specimens, this may prove tricky. A small disgorger, suitable for both the hook size and mouth of the fish can be used whilst simply holding the line, keeping the fish in a bucket of water or still in the sea/rock pool whilst doing so. Alternatively, companies like Majorcraft now produce ‘Fish Grips’ for small species, many of which have annoying spines even if they do not prove to be venomous. A good blog on this product can be found written by LRF expert Ben Bassett on his own website here. It covers the species you should and should not consider using grips for.

Stingray

The spine, or spines, on a stingrays tail really shouldn’t cause anyone much issue, but it can be a daunting prospect dealing with your first one.

The first thing to note is that the spine is not at the very end of the ‘whipping’ tail, but half way down. It’s very visible on most, a large spine laid flat upon the top of the tail. This gives a safe part of the tail (past the spine) to gab a hold of to stop it whipping about, whilst wrapping a thick wet towel around the tail and spine whilst the fish is handled/unhooked.

The second important fact to note is that you are not safe in front of the fish. There are no safe and unsafe ends. The tail can arch right over their back like a scorpion and get people at the head end, or even in front of it. More often than not, however, the stingray gets itself whilst trying to whip over its back. This is why it is as important for the fish as it is for you to wrap the tail quickly whilst unhooking takes place.

More specific unhooking instructions will be detailed in the following sections, but this should stop you having an unfortunate incident with a stingray. If you do get hit by the spine, it is important to seek medical attention immediately. Stingray barbs can contain bacteria which can prove equally problematic on an open wound.

General fish handling best practice: All species

Wet hands

Only use wet hands or if necessary a wet towel to handle a fish. Dry hands and cloths can cause scale loss, opening the fish up to a greater risk of infection.

Limit time out of the water

Limit the time the fish is out of the water, or unhook within the water where practical and safe for you to do so. Pour water over fish during unhooking to ensure they stay wet at all times, especially on hot days.

Put the fish into water

Have a container of water ready to put the fish into whilst preparing for unhooking. Ensure the water is fresh and cool, not stagnant, warm and deoxygenated.

Use wet mats

Utilise padded unhooking mats or ‘brag mats’ for measuring fish, so they don’t lose scales on abrasive or dry surfaces. Wet the mat!

Use wet slings to weigh fish

Use a sling that fully supports the fish if weighing it. Wet the sling beforehand and zero it on the scales first.

Never use gaffs

Large drop or landing nets are sufficient for all uk species, whilst careful planning of landing spots can ensure large species like common skate can be unhooked without needing to be taken from the waters edge.

Don't lift fish by their gills, spiracles or tails

Fish should be properly supported when held and never lifted by gills or spiracles, which can tear, or by their tail which can damage their spine.

Keep the fish close to the ground

Hold the fish close to the ground for photos, to avoid damage if the fish kicks out and is dropped.

Handling fish correctly is part of good angling. If you want to help someone start their journey the right way, try national fishing vouchers for a guided day, a simple way to gift time on the water while promoting best practice.

General unhooking best practice: All species

Ditch the trebles

Switch lures to single hooks rather than trebles, to aid unhooking.

Favour circle hooks

Where possible, and especially for larger fish, use circle hooks to limit deep hooking.

Crush your barbs

For larger fish, crush any barbs on hooks. This will make unhooking much simpler and so long as a tight line is kept, the barb offers no practical advantage.

Don't pull hooks

Don’t ‘pull’ hooks out when deep hooked, if there is no safe way to remove it, cutting the line as close to the hook as possible is preferable.

Be careful around gills

Only access hooks from the gills, e.g. with flatfish, once you know what you are doing. Gills are sensitive so it presents risks.

Have the right unhooking tools ready

Come prepared with the correct unhooking tools. Disgorgers, long nosed pliers and T-bars according to the species and hook sizes.

General release best practice: All species

Allow a fish time to recover

Place a fish back into the water, holding it until you feel it ‘kicking’ and demonstrating the energy to swim away safely. Never throw a fish back in.

Use a net during recovery

A net can be used to hold the fish from an elevation or side of a boat until it is ready to swim away freely.

Ram Ventilators

Ram ventilators need more specific recovery and are covered specifically in a following section (tuna, thresher sharks etc).

Use live wells for recovery of smaller fish

The use of live wells to recover smaller fish on board a boat is encouraged.

Use descending devices

Descending devices should be used to return any fish on a boat that have suffered barotrauma - More on this in a following section.

Elasmobranch (shark, skate and ray) handling

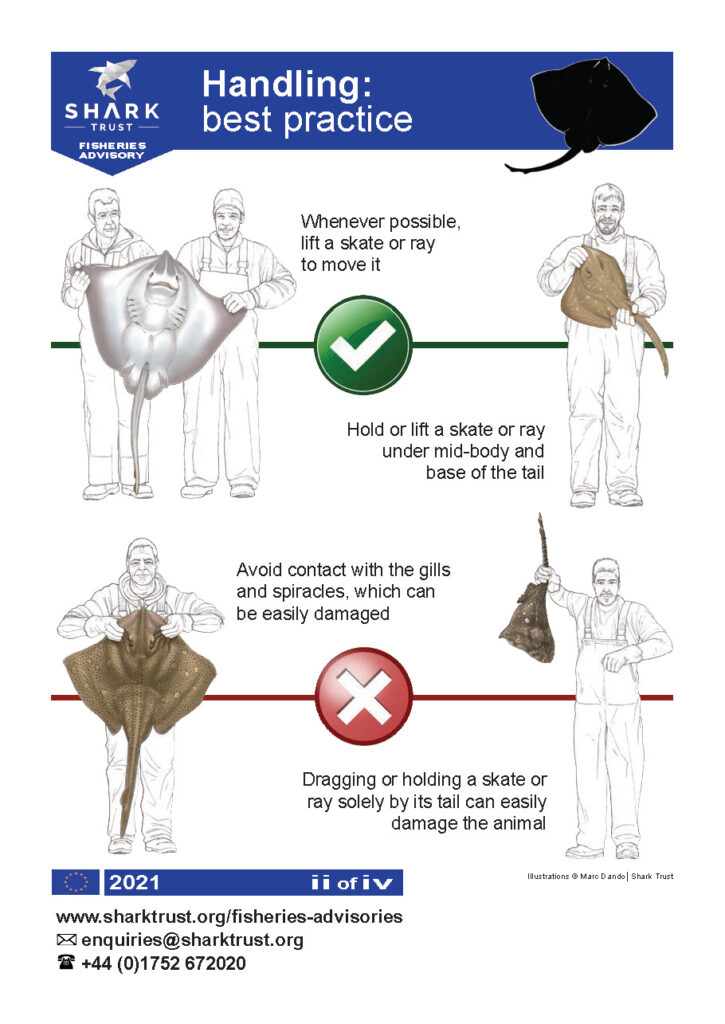

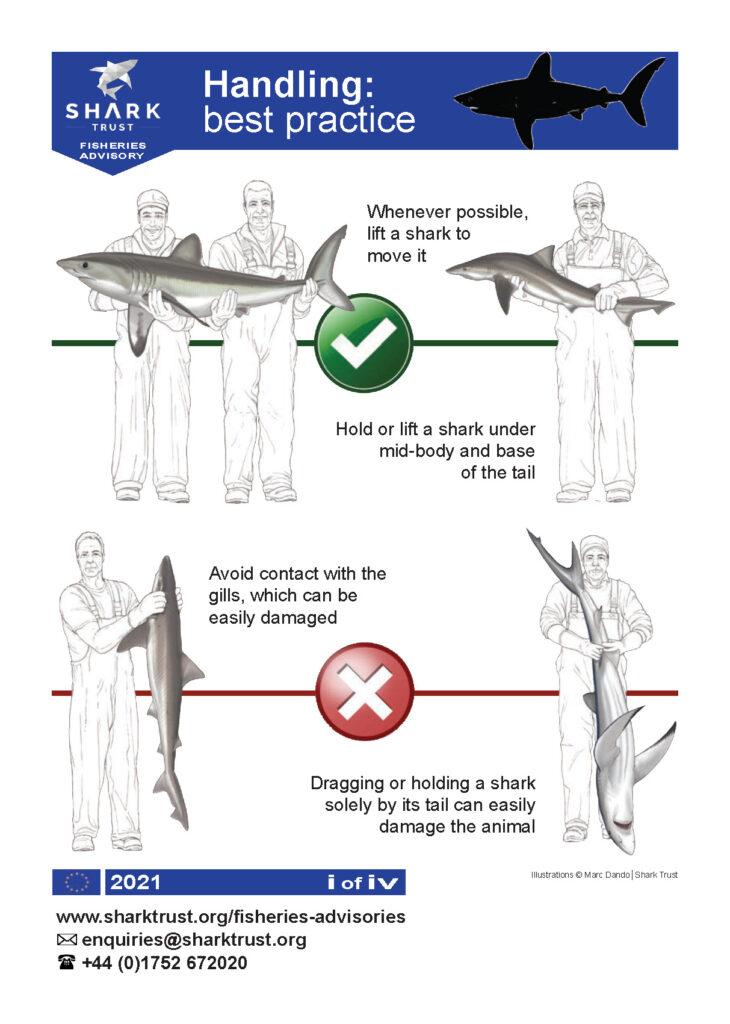

The handling advice produced by the Shark Trust has long since been a reliable standard, so we have included those below. We also suggest visiting their website to view their fisheries advisories, which you can do here.

Key considerations for unhooking sharks, skates and rays

- Do not take large sharks out of the water unless it is absolutely essential, e.g. to remove an entanglement.

- Wire cutters will help with cutting a hook if it really cannot be removed.

- DO NOT place a skate or ray on their back to unhook, you will remove protective slime. With the right tools you will be able to reach under the head of the fish and access the hook.

- Keep your fingers out of mouths of all shark, skate and ray species. Even those without teeth can do significant damage with crushing plates.

- In the case of stingrays, ensure the tail is wrapped and held before starting unhooking, this will protect you and the fish.

- It’s been covered, but to reiterate, NEVER hold a ray by its spiracles or any elasmobranch by their tails.

Obligate Ram ventilation

What is obligate ram ventilation?

Ram ventilation is the process some fish species use to force fresh oxygenated water over their gills, lacking the ability to pump it when stationary. In short, they rely on moving through the water with their mouthes open to ‘ram’ the water past their gills. If these fish stay stationary, they will suffocate, being unable to extract oxygen from the water.

Which species are obligate ram ventilators?

In UK waters, the most prominent species are Atlantic bluefin tuna, porbeagle shark, mako shark and thresher shark. Other smaller species including Atlantic mackerel are also obligate ram ventilators, but the following steps to recover a fish are only suitable to larger species. For smaller species, simply return them to the water as soon as possible with minimal handling.

How to recover an obligate ram ventilator

In very simple terms, get water moving over a fishes gills to recover an obligate ram ventilator. To do this, one must mimic swimming. Whilst the task alone is challenging, it is not suggested to target these fish from the shore as the recovery process is nigh on impossible. From a boat, the process involves securing a fish by the side of the boat, usually with a boga type grip on rope, before towing the fish until it shows signs of recovery, at which point it can be released to swim off.

Should I always recover a ram ventilator in this way?

This comes with experience. The quick answer is no, the less risky answer is yes. There are occasions where a fish comes to the boat green and a quick unhook and release will ensure the fish doesn’t damage itself or angler in the struggle that would ensue to secure the fish to the side of the boat and tow it. Our suggestion is that you don’t target these species without experience or training first. For the very best tuna training available in the UK, contact Crusader Marine here.

Using fish descenders

What are fish descenders?

Fish descenders are a number of devices, from the very basic manual, through to depth triggered devices, for the return of fish to deeper water. These are typically used with fish that have come up from a depth and are showing signs of barotrauma.

What is barotrauma?

Rather than a scientific definition of gases and pressure, it is better to describe what you may have witnessed. A fish with scales standing outright, bulging eyes and a prolapsed swim bladder is suffering from barotrauma. This happens when they cannot regulate the pressure changes after being retrieved from a depth.

How do fish descenders help?

The descender will return the fish to a depth where it’s body can once again equalise with the pressure around it. The recoveries are remarkable and have been captured on camera. A fish that looks beyond help on the surface suddenly reverses symptoms and swims off. Tagging has repeatedly proved a high post release survival when using these devices.

Where do I get a fish descender?

They are relatively new to the UK market, but Veals Mail order stock the more basic option here, or the automatic depth triggered release option here.

How do I use a descender?

We suggest looking at the ‘Return em right’ website for a conclusive look at the use of these devices. A sample video is below.

Handling in Match Fishing

Match fishing carries some specific concerns and considerations for fish handling, owing to the priority of speed, coupled with a need to either retain, measure, weigh or photograph a fish for competition recording. The risks of poor handling are greater in this environment, but good planning can mitigate. Match organisers should have fish handling at the forefront of their minds when developing rules for angling matches, rather than relying on the consideration of each angler.

A match or competition should still account for all of the handling guidelines covered above. The following considerations are additions to help match anglers and organisers in specific match scenarios.

Retention (return to scale) matches

If you are still running matches that require anglers to bring fish back to the scales, even when kept alive for release, you should reconsider this practice. There are no ‘best handling tips’ when it comes to retaining a fish in a warming (or cooling) bucket of limited space, with limited oxygen supply and a high rate of post release mortality. Neither is there justification for selective retention matches, such as ‘single best specimen’, that often sees fish come back to the scales that would otherwise not be chosen for the table. Retention of weight is incentivised over quick dispatch in such scenarios. Alternative mechanisms for matches are mentioned below.

Measure and release

On the face of it, this method sounds an effective method of fishing a match with a good eye on conservation. A quick measurement is taken of the fish and it can be released after witnessing. The potential risks here relate to maximising every last cm on the measure, speed and how it incentivises targeting juveniles of species that have a lower rate of post release survival.

Measure and release match organisers should consider these issues and ensure their rules put sufficient mitigation in place. We cannot cover every possibility here as each match is unique, but some ideas are:

- Introduce species specific minimum sizes to dissuade targeting of juveniles

- Introduce minimum hook sizes to prevent the hooking of juveniles and limit deep hooking of larger fish

- Put a cap on how many of each species will count

- Ensure fish are signed for and released before an angler can cast back out, ensuring the fish does not wait around out of the water unnecessarily

- Record fish in size brackets to disincentivise stretching fish to gain every last cm

- Consider disqualifications for clear basic handling breaches, e.g. tearing/pulling hooks out, throwing fish back in the water, stretching out huss/dogfish/hounds

Weigh and release

This is a much rarer format of match than measure and release, but typically used for matches involving larger specimens. Many such matches have moved to a ‘measure and convert’ system, that uses a table to convert to a weight, an encouraged move. When it comes to weighing fish in such a match, all handling guidelines covered apply, but particular focus in match rules should be placed on the time the fish is out of the water and the requirement to use slings to weigh fish.

Species hunts

These can exist in two distinct formats, either a time limited event, typically aboard a boat, or a more open ended event over a week, month or even the year. Our considerations here focus on the former where speed once again presents the greatest risk of oversight in good fish handling.

Generally, these matches work on the basis of awarding most points for the first of each species caught, with a diminishing amount of points for any fish of that species thereafter. It is a popular format in forces and international boat fishing events and well known by top match anglers.

Being primarily used on boat competitions, the skipper will often act as a competition steward, helping to ensure fish can be quickly witnessed and returned. It can be a very good format for match handling, when the following common rules are implemented:

- A touched leader and witness of the species by the skipper or fellow angler counts. This allows for in-water release of many fish.

- Similar species are counted as one, saving time out of the water spent on identification. e.g. pouting and poor cod, all gobies etc.

- Caught fish only to be retained as bait if immediately dispatched, save for events permitting live baiting.

- Blatantly poor handling leads to disqualification.

Other formats

There are blends of the above formats in use, the key message is to ensure the rules don’t incentivise poor handling. If in doubt about your match rules, you can email enquiries@youranglingvoice with a copy of your match rules for a free bespoke review. This may help in any discussions with local councils for use of specific areas for shore based matches.

Dispatching fish

Appropriate dispatch of a fish is beneficial to both fish and angler. Failure to dispatch appropriately will lead to unnecessary trauma for the fish and a severe drop in quality of the flesh for consumption or even bait purposes. Swift and effective dispatch is therefore key.

There is little point in sugar coating these following points, but for those with no interest in taking fish for the table or for bait, scroll on. For everyone else, you are dispatching a living animal, it’s going to involve blood of varying degrees subject to the species.

If you are intending to take a fish for the table, or for bait, immediate dispatch is critical. Leaving the fish to slowly suffocate is not acceptable and will only ruin the quality of the end product whilst showing our sport in a poor light. Dispatch and chill promptly.

- First, check you can retain the species. Check minimum sizes and bag limits, which can be found here.

- Take a sharp knife and insert it directly between the eyes, press down hard and rotate. This should instantly kill the fish. OR use a sufficiently heavy priest to strike the head of the fish in one quick forceful blow. It should be enough to physically dent the head and immediately cease movement (other than twitching) of the fish.

- Some movement from the fishes nerve system may remain, usually as twitches.

- Bleed the fish by removing the tail and hanging the fish up to utilise gravity. Some will cut a gill or slice the neck, but if the fish is already dispatched this won’t be as effective as it relies on the heart still pumping the blood.

- Remove the guts of the fish by inserting a knife into the anus of the fish and bringing it all the way up to the adjoining of the gills, then cutting out the guts. Early removal of the guts prevents worms migrating from the gut to the flesh.

- Lay the fish on ice, or in a cool environment – You will want the fish to firm up a bit before filleting.

Marine Planning - Angler Engagement and Consultancy:

Helping marine licence applicants secure stakeholder support by meaningfully engaging the UK’s recreational sea angling community.

Dedicated Consultation Representation & Advocacy:

Professional consultation responses that give coastal communities and interest groups a stronger voice in marine decision-making.

Angling Market Integration & Product Development:

Helping marine brands and events successfully connect with the UK’s thriving recreational sea angling sector.

YourAnglingVoice is a trading name of National Fishing Voucher, company number: 15931819.Registered address: 27 Jasmine Way, Weston-super-mare, BS24 7JW