Response to Southern IFCA Black Bream Consultation

The following is our response to the Southern IFCA Black Bream Consultation. Below our response, you will find some guidelines on how you can submit your own thoughts on this consultation. We do not suggest a simple copy and paste of our own, or any other template as they rarely get considered as more than one response, but you can certainly take inspiration from our own.

Alternatively, we can draft a personalised response for you. We’ll arrange a phone call, take some notes on the points you wish to get across, and send you a personalised response by email, or submit it directly on your behalf. Simply add this option to the cart below.

Our response

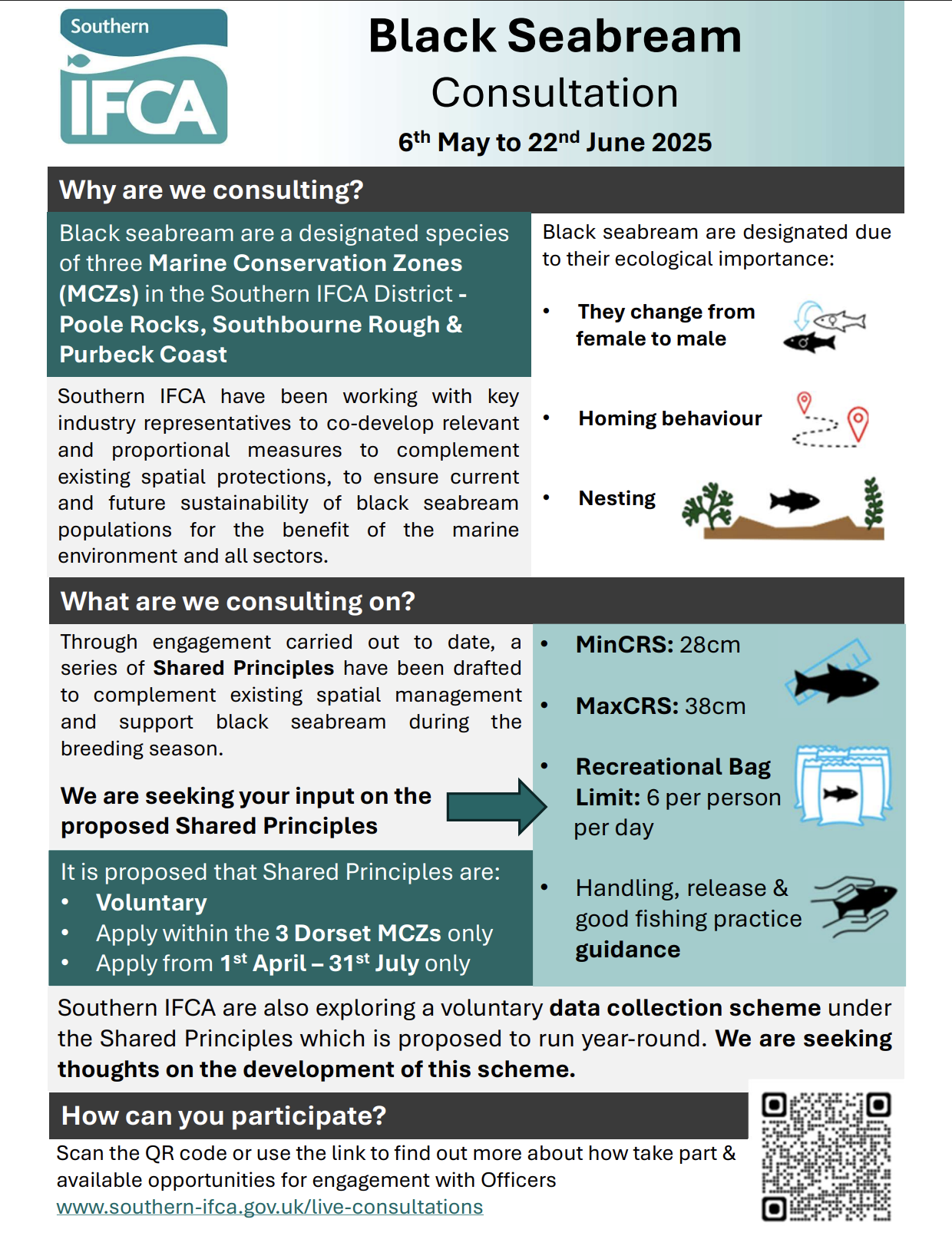

YourAnglingVoice welcomes the opportunity to respond to Southern IFCA’s consultation on voluntary conservation measures for breeding black bream in the Poole Rocks, Southbourne Rough and Purbeck Coast MCZs. Black bream (Spondyliosoma cantharus) is a highly valued recreational species and a critical element of the local charter-boat economy.

We note that all three designated MCZs were created to protect the unique spring spawning aggregations of black bream, which unlike most fish species, ‘nest’ to rear their young.

We strongly support the intent of measures that help ensure the fishery’s sustainability, provided they are clear, equitable, enforceable, and developed in full partnership with the angling community. Below we comment on each proposed ‘shared principle’ and suggest enhancements. We have aimed to keep our comments constructive and technically accurate, recognising that in practice any voluntary code will succeed only if it enjoys broad angler buy-in and clear communication.

Proposed ‘Shared Principles’

Southern IFCA’s Proposed Shared Principles for April – July (bream spawning season) comprise:

- Slot Size: Minimum Conservation Reference Size (MCRS) 28 cm; Maximum CRS 38 cm (28–38 cm slot).

- Bag Limit: 6 fish per person per day (within the slot).

- Handling & Release Guidance: Voluntary best-practice advice for landing, handling, and releasing bream.

These measures, all voluntary, apply only within the three Dorset MCZs during the closed season. We encourage anglers and stakeholders to review each point critically. In general we agree with the precautionary goals of slot limits and bag limits, but emphasise that effectiveness will depend on enforcement, communication, and the broader management context (including commercial quotas under the forthcoming Fishery Management Plan). We offer the following observations and recommendations:

Slot Size (28–38 cm)

The proposed 28–38 cm slot aims to allow at least one spawning cycle (bream reach sexual maturity near ~24 cm) and protect the largest males, which guard the nests. We have no fundamental objection: the minimum 28 cm is higher than earlier IFCA sizes, and exceeds the scientifically-estimated breeding size. Protecting larger males should aid stock recovery, since anecdotal reports show many small bream but fewer ‘specimen’ size fish in recent years. This slot thus balances conservation with reasonable angler retention of table-sized fish.

However, rigid size limits can interact oddly with actual catch-and-release practice. For example, a small deep-hooked bream (say 26 cm) is unlikely to survive catch-and-release compared to a larger lip-hooked fish (say 32 cm), but the measures would reverse the logical nature applied by the angler on which fish to retain.

Our community prefers to return lightly hooked fish (even if big), in favour of keeping deep hooked ones with poor survival prospects, regardless of size; a practice that actually maximises survival. Strict slot definitions make that counter-intuitive choice appear non-compliant.

We therefore suggest Southern IFCA consider wording that acknowledges ethical catch selection. For example: “Anglers are encouraged to prioritise fish unlikely to survive on release (e.g. deep-hooked fish) when choosing which fish to keep within the slot.”

This could be included in the Good-Practice Guidance (see below). We also note that future management actions (e.g. the DEFRA-backed Black Bream Fisheries Management Plan) may introduce new size or gear rules for all sectors. It may confuse anglers if rules are rolled out piecemeal. Once extensive education on voluntary codes is underway, introducing new legal rules could “muddy the waters” for the public. We therefore suggest coordinating the timing of these voluntary measures with any FMP announcements, or at least clearly explaining their interim nature.

Key Points on Slot Size:

- 28–38 cm slot is generally reasonable and should let each fish spawn once.

- Emphasise that large mature males are being protected (they guard the nests).

- Consider an exception/guidance note for ethically releasing lip/light hooked large fish (survival is high).

- Clarify interaction with incoming FMP rules to avoid confusion.

Recreational Bag Limit (6 fish/day)

We support a modest bag limit of 6 fish per angler per day (within the slot). Similar or lower daily limits are standard in MPAs and regulated fisheries (e.g., Sussex IFCA set 4/day in Kingmere MCZ). Such limits are widely used to ensure the benefits of each fish are shared among many anglers for years to come, rather than accumulating catches by a few and damaging the stock over a short period.

The challenge is monitoring and compliance. Under a voluntary regime, how will officers or peer groups verify that an angler has not already kept 6 bream that day? Charter boats often fish multiple marks (both inside and outside MCZs) in a single trip, so any boarding after-the-fact cannot easily tell where fish were caught. This means the bag limit relies on self-reporting and trust. In practice, most recreational anglers are conservation-minded and will follow the spirit of the rule. However, even a few publicly noticed violations can undermine confidence.

To strengthen adherence, we suggest:

- Catch Logging: Encourage anglers (or charter skippers) to log their bream catches (date, location, length) in a simple logbook or smartphone app. This data (voluntary submission) can help show overall compliance. We suggest the IFCA promotes the use of the Sea Angling Diary for this, as a ready made tool run by CEFAS.

- Awareness: Prominently display the limit in harbours, tackle shops, and on social media, along with rationale (protecting spawners). Peer influence (see below) can reinforce the norm that “6 is enough.”

- Vessel Checks: Where possible, IFCA officers could incorporate bream-count questions into routine boardings of charter and private boats (even if off-season or outside MCZs). Making it clear that the bag rule is expected throughout the district (not just MCZs) would close loopholes. (Indeed, a stricter but simple district-wide measure would yield unambiguous results). The goal is not to punish anglers but to gather compliance data; even noting “6 per day” stickers on boats or logbooks would signal seriousness.

In summary, the 6-fish limit is not unduly restrictive. Compliance is best achieved through clear communication and community buy-in. We urge Southern IFCA to invest as much effort in outreach on the bag limit as on conducting the consultation and subsequent drafting of the guidelines.

Handling, Release and Fishing Best Practices

We agree that robust guidance on catch-and-release techniques is vital. Indeed, best practices often spread from anglers themselves, not government mandates.

Formalising and promoting these will amplify voluntary compliance. Key points include:

- Gentle Handling: Advise anglers to use wet hands or gloves, support fish horizontally, minimise air exposure, and return fish to water quickly. Removing the hook in-water or using pliers reduces stress. Avoid lifting bream for photos with fingers in the gills aligns with modern angling etiquette.

- Circle Hooks: Encourage use of circle or non-offset hooks when bait fishing. Circle hooks reduce gut-hooking rates in bream. This simple change dramatically improves post-release survival.

- Descending Devices: Bream, though shallow-spawning, can still suffer barotrauma at typical fishing depths. Studies (e.g. on pollack) show that using a descending device returns fish to depth with minimal harm. We recommend conducting field trials with local charter skippers to demonstrate the value of descenders for black bream. If effective, Southern IFCA could partner with angling organisations to distribute a number of free descending devices to Dorset boat anglers (similar to the Angling Trust/MMO pollack scheme). Recipients would be asked to document and share release outcomes via social media to normalise the practice. This “peer‐endorsement” model has proven effective.

- Live Wells: Providing fresh saltwater via live wells aids fish recovery. We encourage Southern IFCA to promote the use of live wells on all charter and private boats during this period. For example, boat owners could be offered simple checklists or posters showing how to monitor oxygen levels and temperature. IFCA might also work with boating groups to offer discounts or grants on live well modifications. If a fish is held briefly to revive (and sadly dies), at least it counts toward the angler’s bag rather than wasting an allowable slot. This idea could be included in the “good practice” code.

In all cases, the guidance should be positive and evidence-based. We recommend co-creating any infographics or leaflets with experienced skippers and anglers. This has worked well for other fisheries in the past. A local charter skipper’s endorsement (“This is how we fish for bream”) resonates far more than a distant bureaucrat’s leaflet. We urge IFCA to enlist well-known local skippers or charter operators as ambassadors for the guidance, perhaps through short videos or port talks. Their voices will give credibility and inspire followers.

Enforcement, Monitoring and Compliance

Southern IFCA should recognise that voluntary measures work best when all stakeholders have “bought in,” but they still require oversight. Parliamentary evidence on UK MPAs makes this clear: voluntary codes can succeed in small, committed communities, but come with a risk of non-compliance unless backed by some enforcement capacity. For example, the Lyme Bay voluntary ban on scallop dredging saw near-universal compliance through peer pressure, but even a single breach led regulators to codify the restrictions for certainty. Conversely, simply writing a law without community engagement rarely guarantees compliance. With this in mind, we suggest the following to support compliance:

- Documentation and Audit: Southern IFCA should explicitly commit to tracking compliance metrics from the start. This could mean keeping records of any boarding outcomes, and conducting random checks to estimate adherence. Transparent “report cards” summarising this data after the first season would build trust: if compliance is high, anglers can see their efforts are working; if gaps emerge, the IFCA can adjust outreach or consider legal backing.

- Integration with Data Collection: The proposed use of the Sea Angling Diary can double as a compliance monitor. For instance, if charter anglers submit catch logs as part of the scheme, IFCA staff can analyse catch-per-unit-effort and bag-limit reports over time. Southern IFCA should facilitate this by incentivising the use of Sea Angling Diary in the district, such as through prize draws (e.g. for submitting logs) would boost participation.

- Continuous Engagement: Enforcement is not just about sanctions. Every contact with an angler should be educational. IFCA officers boarding a vessel (for any reason) can take a few minutes to remind anglers of the code, collect catch data, and answer questions. If a breach is observed, an initial approach could be a friendly reminder (given the voluntary context). Over time, courtesy reminders reinforce that the IFCA is serious, but also reasonable. In any future consultation on a byelaw, this history of voluntary enforcement will be valuable evidence.

Some anglers may question why we would be requesting greater checks on enforcement for voluntary measures, but it is clear that if we cannot evidence compliance then the IFCA will, in the future, pursue legislated measures. The IFCA must not set us up for failure, it must have a clear and accurate way to measure compliance from the outset if the principle of voluntary uptake is not to be undermined.

Southern IFCA should make clear that these “principles” are a step toward statutory management if needed and Anglers must understand that agreeing to the code is the best way to avoid stricter byelaws later. Transparency on the process from the outset is essential.

Angler Engagement & Communication

Effective communication is the linchpin of voluntary success. We urge Southern IFCA and partner organisations to:

- Leverage Local Champions: As noted above, we should “tell the story” through trusted local anglers. Publicise charter skippers who already practice voluntary release and catch logging. Short testimonials (e.g. a local angler blog post or social media video) on why they support the code can influence peers more than government press releases. The nature of improvements in UK shark angling is a good model: industry leaders informally changed behaviour, which was later formalised in guidance.

- Use Social Media Positively: Monitor channels (Facebook groups, fishing forums, Instagram) for misinformation or anger, and respond promptly. Instead of letting negative posts define the narrative, flood feeds with positive examples: e.g. feature positive supportive posts of anglers releasing big bream, charter crews using descending devices, or catching their “limit” responsibly. Southern IFCA might run a lighthearted photo contest (“Biggest Released Bream of the Week”) with prizes from local tackle shops. Encouraging anglers to post their compliance (with a hashtag) turns them into advocates.

- Community Meetings and Outreach: Present clear, engaging materials: diagrams of size-limits, Q&A on how to use descenders, etc. Run events to sign up anglers for the data scheme or voluntary code pledge. Invite charter boats to display campaign posters on their vessels, turning the fleet itself into a walking billboard of best practice.

- Collaboration with Angling Clubs: Work with local sea-angling clubs to hold workshops or talks. These trusted club environments are ideal for Q&A.

In short, avoid the “printed leaflet drop” approach alone. Leaders within the community must own the initiative. When skippers say “this is how I fish for bream,” everyone listens. Persuading anglers that the measures are in their interest is what truly achieves compliance.

Incentives & Angler-led Initiatives

Beyond education, positive incentives can accelerate uptake:

- Equipment Giveaways: As above, distribute free descending devices (e.g. via a sign-up raffle) to Dorset boat anglers. Partner with UK tackle brands or explore the upcoming coastal and fishing development fund to fund a supply of descenders and perhaps basic live-well maintenance kits. In exchange, participants agree to post on social media or share catch logs.

- Prize Draws for Reporting: Encourage anglers to submit voluntary data by running monthly prize draws: e.g. “Submit your bream log this week for a chance to win a charter trip” (local charters might sponsor). Incentives that directly support anglers (gear, vouchers) motivate participation more than generic appeals.

- Recognition Schemes: Establish a “Black Bream Steward” certification for charter boats or private anglers who adhere to the code and log catches diligently. This could be a decal or online certificate; charters could display it to advertise their conservation ethics. Customers may even prefer boats with such a label. recognition. This is a recreational charter level equivalent of the MSC ‘blue tick’ that commercial fisheries strive to achieve.

- Storytelling and Visibility: Profile success stories in angling media: for example, a monthly update on bream in national angling blogs. If an angler released a tagged bream or a big keeper that met the slot, celebrate it. Positive news counters negativity.

These mechanisms build social capital around the voluntary code. They echo the the Lyme Bay “Reserved Seafood” scheme where data provenance created market value. While a wild fish market is not the goal here, the principle is the same: reward good practice.

Marine Protected Area Context & Habitat Corridors

We urge Southern IFCA and DEFRA to consider spatial protections in tandem with these voluntary rules. Black bream migrate seasonally between the Isle of Wight, Poole Bay and Purbeck reefs. The current MCZs protect key nesting sites, but leave Poole Bay, a central corridor, largely unprotected. This gaping hole is exploited by mobile fishing (e.g. beam trawl) that can impact bream on migration routes.

A concrete recommendation is to extend MCZ protections to encompass Poole Bay. For example, designating the entirety of Poole Bay as an MPA with a bottom-trawl ban would create a safe corridor linking the known breeding grounds. This would benefit bream and many other species. It could be proposed for formal consideration in IFCA plans. At minimum, Southern IFCA should reaffirm that within the three MCZs there is currently zero commercial bream fishing allowed (if that is indeed the case), to address anglers’ concern that “released” fish might simply be re-caught by commercial boats. Publicly clarifying the full suite of protections (recreational and commercial) would improve buy-in.

Data Collection & Adaptive Management

Southern IFCA’s plan to create a voluntary year-round data-collection scheme for black bream is highly welcome.

Comprehensive catch data will be critical for adaptive management. We suggest:

- User-Friendly Platform: The system should be accessible (smartphone app + web form) and quick to use. Anglers hate lengthy forms; a simple “record catch length, method, location, live/dead” entry will yield more data. Partnering with the Sea Angling Diary would expedite this, though we would highly recommend increasing the measures on the socio-economic side. It isn’t all about extraction, but the value that derives for coastal communities.

- Citizen-Science Approach: Frame data collection as a citizen-science project. Highlight how the community has contributed to other successes. Offering periodic feedback on the data (“In 2025, anglers reported X black bream of average length Y”) will reinforce its value.

- Tagging and Surveys: Consider a tag-and-recapture program in partnership with local universities and seek any available funding under the Coastal and Fishing Development Fund. Rewarding anglers with tags to release bream (with a small tag-reward) could yield movement and mortality data.

- Link to Management: Make clear that data will inform policy. If catch-per-angler increases (or declines), or if slot compliance is already effective, IFCA can adapt. This can be communicated to anglers so they see their input leading to results.

Taken together, good data will demonstrate whether the voluntary code is working. If it isn’t, it also provides evidence for any future byelaw. This approach follows DEFRA guidance that management measures in MPAs should be evidence-based and developed through consultation.

The Studland Bay MCZ (also in Dorset) is an example: after an assessment and engagement, a voluntary no-anchoring zone was introduced in 2021. Data and stakeholder input made that measure well-targeted. Similarly, a well-publicised data scheme here can build trust that measures are being evaluated rigorously.

Voluntary vs Statutory – A Phased Approach

Lastly, we acknowledge that Southern IFCA has chosen a voluntary approach. As policymakers have testified, both voluntary and statutory measures have roles. We advise Southern IFCA to view this as a phased strategy: start with the voluntary Shared Principles to build habits and goodwill, but be clear that legal byelaws remain on the table if needed. This transparency is critical for anglers to understand why they are being asked to voluntarily take these measures. Parliamentary evidence on MPAs notes:

“There is room for both voluntary measures and statutory codification. In most cases you will need both… Voluntary measures might be helpful where you do not have the capacity to enforce by other means or monitor. It is still an evolving picture… regulators could do more to consider the voluntary approach fairly as part of their deliberations.”

In other words, we should not view this as “voluntary or mandatory” but as a step pathway. The initial voluntary code should be framed as the community’s own agreement, with the understanding that it may be reviewed and backed by law if compliance falls short. This perspective will encourage buy-in rather than resistance (i.e. “this is our code, not an imposition”). It also aligns with DEFRA/MMO practice of using codes of conduct first, then byelaws as needed.

Specifically, if voluntary compliance appears high by mid-July 2026 (measured via the above methods), Southern IFCA can publicise that success, which itself encourages more compliance. If not, a byelaw could be prepared over the autumn with a robust case. In either scenario, the anglers will have been part of the solution.

Summary of Recommendations

- Communicate Clearly: Roll out the Shared Principles with joint messaging from Southern IFCA and local skippers. Explain the why (breeding biology, MCZ purpose) and how in simple terms.

- Involve Anglers: Develop the Good-Practice Guidance in consultation with anglers (via clubs or online workshops), ensuring it resonates with what fishers already do. Use peer testimonials prominently.

- Encourage Tools: Provide or subsidise descending devices and live well improvements for anglers; use social media hashtags and contests to publicise these tools.

- Gather Data: Launch the voluntary catch-recording scheme with incentives; analyse and report results periodically. Use this data to confirm the status of stocks and compliance.

- Strengthen Protections: Consider recommending that Poole Bay be added to existing MCZs (with a trawl ban) to protect migration routes. Clarify that no netting of black bream is allowed in the MCZs during season.

- Support Transition: Treat this as a pilot phase. Explicitly link the voluntary measures to the forthcoming Fisheries Management Plan so anglers see a coherent strategy. Indicate that continued commitment by anglers could defer stricter byelaws.

We believe that by coupling sensible voluntary rules with intensive community engagement and smart incentives, Southern IFCA can achieve near-total compliance and genuine conservation benefit without friction. Reinforce that these measures have been “co-developed with local anglers and skippers”, a vision we fully endorse.

We stand ready to assist Southern IFCA further (e.g. through testing methods, drafting outreach materials, or presenting at meetings) to ensure that Dorset’s black bream receive the protection they need for generations to come. Thank you for considering our comments. We respectfully submit this response and welcome any further dialogue.

Grant Jones, Lead Consultant

YourAnglingVoice

How to submit your own response

Our Services

Marine Planning - Angler Engagement and Consultancy:

Helping marine licence applicants secure stakeholder support by meaningfully engaging the UK’s recreational sea angling community.

Dedicated Consultation Representation & Advocacy:

Professional consultation responses that give coastal communities and interest groups a stronger voice in marine decision-making.

Angling Market Integration & Product Development:

Helping marine brands and events successfully connect with the UK’s thriving recreational sea angling sector.

YourAnglingVoice is a trading name of National Fishing Voucher, company number: 15931819.Registered address: 27 Jasmine Way, Weston-super-mare, BS24 7JW